Pompeii, a city extraordinarily preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D., offers a unique and detailed glimpse into Roman daily life, including its harsher and often neglected aspects. Beyond the elite and the middle class, recent excavations are illuminating the daily lives of the subordinate population, including slaves and children, revealing the spatial constraints and interconnection within which their existence unfolded.

A silent majority: origins and roles

In Roman times—and in Pompeii—slaves made up a largely predominant component of the population, mostly of foreign origin. The city’s first season of prosperity, between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, coincided with the influx of resources from Rome’s wars of conquest: together with booty, enormous masses of slaves fueled the agrarian and manufacturing economy.

Servile labor was omnipresent and diversified:

-

Economy and trade. Prominent figures such as the banker L. Caecilius Iucundus dealt in goods and slaves, collecting rents on behalf of others with commissions between 1–4%. His wax tablets reflect a society in which rank and wealth were tightly interwoven.

-

Production and baking. In the pistrina (bakeries) slaves operated the mills—a task shared with blindfolded donkeys and horses. Even insolvent debtors could be forced to “work at the mill,” as Plautus recalls.

-

Exploitation and vulnerability. The House of the Vettii reveals the shadows of exposed lives: the Greek slave Eutychis, “of good manners,” practiced prostitution inside the house for two asses.

-

Public and religious service. There were also public slaves: Marcus Venerius Secundio served as custodian of the Temple of Venus before his manumission.

Tight spaces, intertwined lives

Recent research has shifted attention to modest environments that sustained the dreams and fears of the majority. Slave quarters, often adjacent to workplaces, are now a privileged object of study; emblematic is the discovery of a “slave room” in a suburban villa.

-

Servile quarters. At Civita Giuliana, about 700 meters northwest of the city, the servile sector of a large villa has reemerged, with a stable and the remains of three harnessed horses.

-

Houses without atria and lofts. Most Pompeian dwellings lacked the canonical atrium: workshops with back rooms, small apartments, lofts. In the House of the Lararium (IX 10, 1) two rooms on the upper floor, reached by a loft, yielded furnishings of extreme simplicity.

-

Public spaces and separations. Even the theater reaffirmed hierarchies: the upper crypta was adapted to accommodate foreigners, slaves, the poor, and perhaps women. Access via modest external stairways prevented mingling with the rest of the audience, in line with the Augustan ideology of strictly separated orders.

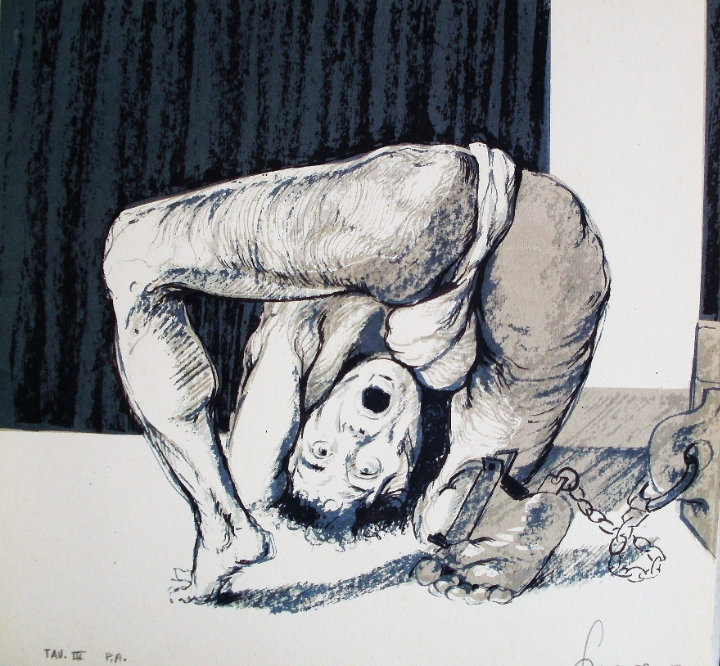

Back-breaking labor: men, women… and animals

In Pompeii, slave labor was often “embedded” in the place of production. The House with Bakery of Rustius Verus (Reg. IX, Ins. 10, no. 1) combines a residential part with high-quality Fourth Style frescoes and a productive sector devoted to baking. Ancient sources (such as Apuleius) evoke the “discipline of the odious workshop” (inoptabilis officinae disciplina): a work organization that choreographed the movements of people and animals. Material traces such as the circular ruts (curva canalis) carved into the volcanic basalt pavement speak to the relentless repetition of the mill rounds.

Fleeting writings, engraved histories

Walls and amphorae speak. Parietal epigraphy—tituli picti and graffiti—is essential for reconstructing exploitation, escapes, and identities. In Insula IX 8 a graffito mentions the escape of a slave; across the broader body of inscriptions, social stratification and the everyday realities of bodies at work come into focus.

Alongside this is a Pompeii of children who observe and reproduce the adult world: in the House of the Second Colonnaded Upper Room (Insula of the Chaste Lovers), charcoal drawings by children aged 5–7 depict gladiators, boxers, and venationes. Not copies of artworks, but childish attempts—the so-called “cephalopods”—to render the blood spilled in the arena: a humanity suspended between handprints on the wall and a time when violence was entertainment for all ages.

Imported religions and support networks

Not identifying with their masters’ cults, slaves and freedmen helped spread imported deities and maintained ties with their own native gods. The cult of Isis was particularly widespread thanks to these groups. For the poorest—slaves included—there were collegia funeraticia (funerary associations): monthly contributions to guarantee a funeral and the associated rites. Even men of low status could wear the toga at funerals—at least in theory—as a satirist notes, for many it was the only occasion.

The road to freedom: the rise of freedmen

Slavery was not an immutable condition. Pompeian society displayed strong social mobility: freedmen (liberti) could achieve notable status and wealth, often embracing a more direct, “plebeian” taste in figurative culture. In the city’s final phase, the freedman class reached a high point: in various Italic centers, families of freedmen became part of a new plutocracy.

Emblematic cases of upward mobility:

-

Marcus Venerius Secundio, once a public slave and custodian of the Temple of Venus, became an Augustalis after manumission, gaining prestige and means.

-

Numerius Popidius Ampliatus, probably a freedman without access to magistracies, amassed wealth—likely through trade—sufficient to rebuild the Temple of Isis after the AD 62 earthquake. In return, his son Numerius Popidius Celsinus, just six years old, was appointed decurio, setting him on the path to the city’s aristocracy.

After the AD 62 earthquake, many wealthy families left Pompeii, entrusting the management of their damaged assets to their freedmen. The protracted reconstruction paved the way for “social climbers” and for owners of medium-sized houses who had rapidly accumulated wealth through commerce and business. In parallel, a transformation in housing—“houses without atria” in the Insula of the Chaste Lovers—reflected new residential models shaped by freedmen and merchants.

The eruption and after: labor even amid disaster

The catastrophe of AD 79 spared no one. Yet, in the immediate aftermath, when survivors—or those returning to recover objects—moved among the ruins, slaves were employed to strip houses more efficiently: one more turn of servile labor within tragedy.

Conclusion: material traces of difficult lives

The life of slaves in Pompeii shows how rank and wealth determined every aspect of existence: from being born into servitude to the attempt at ascent through manumission, shared cults, funerary networks, and—at times—family advancement. The material and epigraphic traces of these lives, often silent and difficult, tell of a city where servile labor sustained prosperity, while children, women, and men internalized—and sometimes overcame—an everyday reality of constraints, separations, and hopes.

Context references cited in the article

-

Banker L. Caecilius Iucundus (wax tablets; slave trading; 1–4% commissions).

-

House of the Vettii (Eutychis, prostitution).

-

Public slave: Marcus Venerius Secundio (later Augustalis).

-

Civita Giuliana (servile sector; stable with three harnessed horses).

-

House of the Lararium (IX 10, 1) (simple rooms; loft).

-

Theater (separate spaces for slaves, foreigners, the poor, and perhaps women in the upper crypta).

-

House with Bakery of Rustius Verus (Reg. IX, Ins. 10, no. 1) (coexistence of residence/production).

-

Insula of the Chaste Lovers (houses without atria; children’s drawings in the House of the Second Colonnaded Upper Room).

-

Collegia funeraticia; cult of Isis spread by slaves and freedmen.

-

Numerius Popidius Ampliatus and Numerius Popidius Celsinus (rebuilding the Temple of Isis; appointment as decurio).

-

Post-eruption: use of slaves in stripping houses.

FAQ – Slaves and Freedmen in Pompeii

Who were most of Pompeii’s slaves?

Largely of foreign origin, they arrived especially following Rome’s wars of conquest in the 3rd–2nd centuries BC, when the influx of slaves fueled the agrarian and manufacturing economy.

Which sectors did they mainly work in?

Everywhere: in commerce (as in the operations of banker L. Caecilius Iucundus, who also dealt in slaves and collected rents with 1–4% commissions), in production (especially mill-bakeries), in public and religious service (public slaves assigned to temples), and even in activities tied to sexual exploitation, as the case of Eutychis in the House of the Vettii shows.

What does pistrina mean?

It is the bakery equipped with mills and ovens. Here, slaves drove the millstones together with blindfolded donkeys or horses; in some cases, insolvent debtors were forced to “work at the mill.”

What is the curva canalis mentioned for the mills?

They are the circular ruts carved into the volcanic basalt paving by the ceaseless rounds of people and animals around the mill: material marks of the “discipline of the odious workshop” recalled by Apuleius.

Where did slaves live?

Often in quarters attached to workplaces or in dedicated rooms of extreme simplicity. Recent examples include the “slave room” in a suburban villa and the servile spaces of the villa at Civita Giuliana, with a stable and the remains of three harnessed horses.

Did Pompeian houses always have an atrium?

No. Many were workshops with back rooms, small apartments, and lofts. The House of the Lararium (IX 10, 1) shows upstairs rooms reached by a loft with essential furnishings. Excavations in the Insula of the Chaste Lovers have also revealed “houses without atria,” indicating housing models linked to freedmen and merchants.

How did segregation work in public spaces?

In the refurbished theater, the upper crypta hosted foreigners, slaves, the poor, and perhaps women. Access via modest external stairways prevented mingling with the rest of the audience, consistent with the Augustan ideology of separate orders.

What role did slaves and freedmen play in religious cults?

They helped spread imported deities, seeking protection in cults alternative to those of their masters. The cult of Isis is the clearest example.

What were the collegia funeraticia?

Associations to which members—including slaves and freedmen—paid monthly contributions to secure funerals and rites. At funerals, even men of low status could wear the toga, often the only occasion in their lives.

Was slavery forever?

No. Manumission was possible and with it social mobility. The freedman class grew strongly in Pompeii’s final phase, at times reaching an urban plutocracy.

Who are some emblematic freedmen?

Marcus Venerius Secundio, a former public slave and custodian of the Temple of Venus, became an Augustalis. Numerius Popidius Ampliatus financed the rebuilding of the Temple of Isis after AD 62, securing for his son Numerius Popidius Celsinus (six years old) appointment as decurio.

What is the link between the AD 62 earthquake and the rise of freedmen?

After the quake, many wealthy families left Pompeii and delegated the management of their assets to their freedmen. The long reconstruction favored the rise of newly enriched individuals and owners of medium-sized houses, often tied to trade.

What do graffiti and inscriptions tell us about slavery?

Tituli picti and graffiti are fundamental for reconstructing exploitation, escapes (as in Insula IX 8), and social dynamics. They are “fleeting writings” that preserve stories otherwise invisible.

How did children reflect the culture of violence?

In the House of the Second Colonnaded Upper Room (Insula of the Chaste Lovers), charcoal drawings by children (ages 5–7) show gladiators, boxers, and venationes: not copies of art, but visual memories of brutal spectacles—the “blood spilled in the arena.”

Do slaves appear even after the AD 79 eruption?

Yes. During the stripping of houses, survivors or those returning to retrieve objects employed slaves to facilitate operations among the ruins.

What does Augustalis mean in the case of Marcus Venerius Secundio?

A member of the priestly college in charge of the imperial cult. For a freedman, admission among the Augustales signaled prestige and public recognition.

Why are “houses without atria” important for understanding Pompeian society?

Because they indicate a shift in housing models linked to the rise of freedmen and merchants, less interested in the atrium’s display and more in the practical needs of integrated work and residence.

What does the “slave room” teach us?

That servile everyday life unfolded in tight spaces, functional to labor. The analysis of these rooms—poor furnishings, proximity to productive areas—sheds light on rhythms, habits, and relationships of dependency.

Why is the House with Bakery of Rustius Verus a textbook case?

Because of the coexistence of a well-appointed residential sector (Fourth Style frescoes) and an intensive productive sector: a microcosm where the movements of slaves and animals were choreographed by infrastructures such as rotation ruts.

What are the limits of our knowledge?

Sources are partial and often filtered through the elite’s viewpoint; hence, recent excavations of modest spaces—servile quarters, workshops, lofts—are crucial for restoring the voices, gestures, and objects of the silent majority.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Adam J.P., Osservazioni tecniche sugli effetti del terremoto di Pompei del 62 d. C, in I terremoti prima del Mille in Italia e nell’area mediterranea, SGA, Bologna, 1989, pp. 460-74.

• Amoretti V., Comegna C., Iovino G., Russo A., Scarpati G., Sparice D., Zuchtriegel G., Ri-scavare Pompei: nuovi dati interdisciplinari dagli ambienti indagati a fine ‘800 di Regio IX, 10, 1, 4, in E-Journal degli Scavi di Pompei, 2, 2023.

• Amoretti V., Comegna C., Iovino G., Russo A., Scarpati G., Sparice D., Zuchtriegel G., Ri-scavare Pompei: nuovi dati interdisciplinari dagli ambienti indagati a fine ‘800 di Regio IX, 10, 1, 4, in E-Journal degli Scavi di Pompei, 2, 2023.

• Bravaccio C., Comegna C., De Rosa S., Gison G., Russo A., Scarpati G., Sparice D., Zuchtriegel G., Scene di un’infanzia pompeiana. Nuovi scavi nel cortile della Casa del Secondo Cenacolo Colonnato nell’insula dei Casti Amanti, in E- Journal degli Scavi, 13, 2024.

• Castrén P., Ordo Populusque Pompeianus. Polity and Society in Roman Pompeii, Roma, 1975.

• Della Corte M., Case ed abitanti di Pompei, Napoli, 1965.

• D’Alessio M. T., Bianco R., Bossi S., V. Bruni, E. Pavanello, Architetture e paesaggi urbani a Pompei: Il Sistema informativo dell’Università Sapienza di Roma per l’analisi, la conoscenza e la gestione del patrimonio archeologico: l’Atlante della Regio VII, in E-Journal Scavi di Pompei, 25, 2024.

• Franklin Jr. J.L., Fragmented Pompeian Prosopography: The Enticing and Frustrating Veii, in The Classical World, 98, 2004, pp. 21-29.

• Iovino G., Marchello A., Trapani A., Zuchtriegel G., La disciplina dell’odiosa baracca: la casa con panificio di Rustio Vero a Pompei (IX 10, 1), in E-Journal degli Scavi di Pompei, 8, 2023.

• Kruschwitz P., Reading and writing in Pompeii: an outline of the local discourse, in Studi Romanzi, 10, 2014, pp. 245-79.

• Maiuri A., L’ultima fase edilizia di Pompei, Roma, 1942 (rist. Napoli 2002).

• Monteix N., Pompéi, Pistrina: Recherches sur les boulangeries de l’Italie romaine, in MEFRA, 122, 1, 2010, pp. 275-282.

• Mouritsen H., Elections, Magistrates and Municipal Elite. Studies in Pompeian Epigraphy, Roma, 1988.

• Osanna M., Muscolino F., Si ritorna a scavare a Pompei: le nuove ricerche della Regio V, in Ricerche e scoperte a Pompei. In ricordo di Enzo Lippolis, Roma, 2021, pp. 139-152.

• Scappaticcio, M.C., Voci dell’altra Pompei: leggere il patrimonio scritto, in L’altra Pompei. Vite comuni all’ombra del Vesuvio, Napoli, 2023, pp. 110-114.

• Stefani G. c.s., Per un aggiornamento dell’indirizziario di Pompei. Il caso della tomba a shola di “Mamia”, in Rivista di Studi Pompeiani, 35.

• Torelli M., Le tombe a schola di Pompei. Sepolture “eroiche” giulio-claudie di tribuni militum a populo e sacerdotes publicae, in RA, 70.2, 2020, pp. 325-358.

• Varone A., Stefani G., Titulorum pictorum Pompeianorum qui in CIL vol. IV collecti sunt: imagines, Roma, 2009.

• Zanker P., Pompei, Milano, 1993.

• Zuchtriegel G., Comegna C., De Rosa S., Scarpati G., Spinosa A., Terracciano A. 2024 b, Case senza atrio a Pompei. Un nuovo esempio dalle ricerche in corso nell’Insula dei Casti Amanti, in E-Journal degli Scavi di Pompei, 26, 2024.

• Zuchtriegel G., Nuova luce sulla Villa dei Misteri: dal restauro alla conoscenza di un capolavoro dell’arte “post-ellenistica”, in Rispoli M., Zuchtriegel G. (a cura di), I cantieri di Pompei. Villa dei Misteri, Napoli, 2024, pp. 9-30.

• Zuchtriegel G., Scavando a Pompei. La casa del Tiaso e il suo mondo, Firenze, 2025.